Scroll down to hear our interview!

Keener original, Robin Seymour, has written a long awaited autobiography. “The DJ That Launched 1,000 Hits” is a fascinating read and a required addition to the library of every true Keenerfan. We caught up with Robin, now in his 9th decade of life, for a taste of the treasures to be found in his extraordinary memoir.

Keener original, Robin Seymour, has written a long awaited autobiography. “The DJ That Launched 1,000 Hits” is a fascinating read and a required addition to the library of every true Keenerfan. We caught up with Robin, now in his 9th decade of life, for a taste of the treasures to be found in his extraordinary memoir.

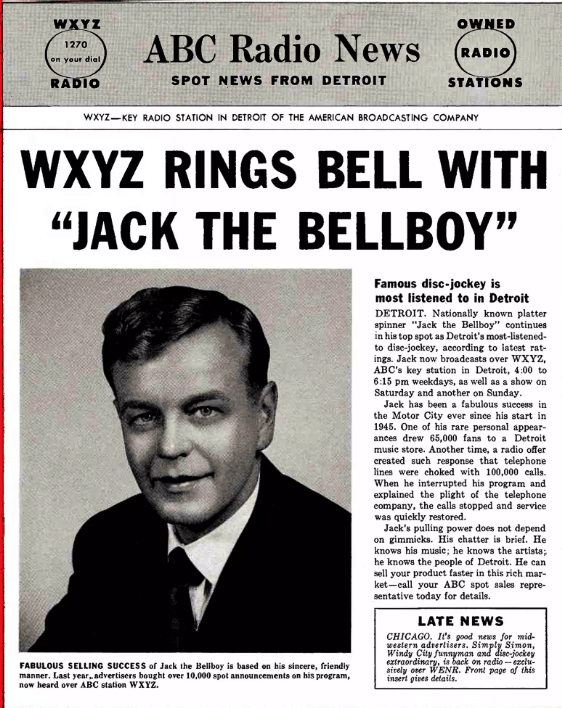

Child radio actor disk jockey television star, rock band manager, marketer, infomercial trailblazer and author; All of these apply to the renaissance man that is Robin Seymour. At the time of our visit, Robin was in his 90s, one of the last living connections to the original staff members at Keener’s predecessor, WKMH (Lee Alan, Dave Prince, Paul Cannon, Bill Phillips, Ray Otis and Jim Sanders and Bob Green are other notable names). His memories of a career that spans over 8 decades were still sharp, as is his recollection of a pivotal conversation with WJBK legend Ed McKenzie. The man who portrayed the station’s popular “Jack The Bellboy” said to the teenage weekend part timer, “So you think you want to make radio a career? Don’t. You will always be on the outside looking in.”

That challenge spurred the former child radio actor, who played the Lone Ranger’s nephew on WXYZ to prove his mentor wrong.

Robin Seymour says it wasn’t until he won a part in a school play that he realized that performing would give him the identity and the friends that a painfully shy youngster found hard to make, growing up in Detroit. “After that one performance, people started to talk to me. I was hooked.”

He leveraged his experience in the school radio club to earn his stripes on the American Forces Network during World War II, experience that would help him take a circuitous route to WKMH around the time that owner Fred Knorr was thinking about programming a disc jockey show in the afternoons. The station was located above a furniture store and next to a church. Robin’s popular music playlist and engaging personality drew students to the studio after school. “At first it was just a few, then it was 10, 20 and eventually became a dance party,” he remembers. “My first radio gig paid 90 cents an hour. When Mr. Knorr offered me the record show, he also offered me a piece of the action. I earned 10% commission on every commercial. That grew into a significant income.”

Robin ended up facing off with Ed McKenzie, the two shared the same time slot on WKMH and WJBK. Ultimately, they became close friends. It was Robin who told Columbia Records about an up and coming singer named Johnnie Ray. He convinced Columbia’s Danny Kessler to make a test pressing of Ray after seeing the artist at Detroit’s Flame Showbar. That lead to a long and profitable career for Ray, who’s music and performance style has been said to be an important precursor to rock and roll.

In fact, Robin met just about every big name who came through Detroit. “During my years at WKMH and Keener, I must have done hundreds of record hops and personal appearances and interviewed literally thousands of artists.”

The first was blues singer “Bull Moose” Jackson, the risqué author of suggestive and often banned tunes like “Big Ten Inch Record”, a song later covered by Aerosmith. “At first I was terrified,” Robin said about the interview process. “My second interview answered every question with ‘yes’ or ‘no” and it felt like it might never end.”

Tommy Dorsey was his next guest and the seasoned big band leader gave Robin the confidence that would radiate across the airwaves in every artist interview that followed. “I was warned that Tommy could sometimes imbibe and the bouquet of bourbon followed him into the studio. But he was terrific and put me right at ease. I’ve never forgotten that.”

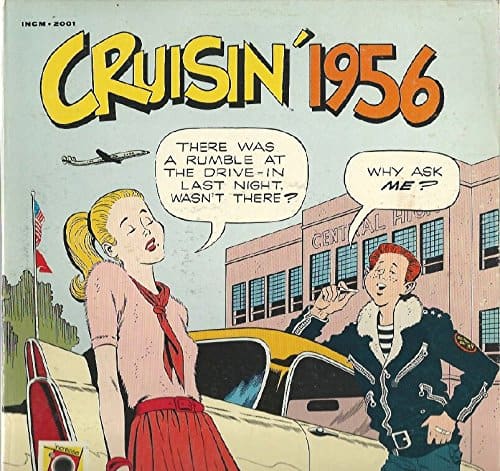

After Fred Knorr’s untimely death, the new general manger, Walter Patterson, took Robin to dinner to ask his advice on what to do to make WKMH more successful. The two had been friends since the days when Robin introduced Walter, who played the big grand piano that was once a fixture in the WKMH studios. Robin’s WKMH vibe was showcased in the second of the Cruisin LP series, featuring WKMH and the year 1956.

After Fred Knorr’s untimely death, the new general manger, Walter Patterson, took Robin to dinner to ask his advice on what to do to make WKMH more successful. The two had been friends since the days when Robin introduced Walter, who played the big grand piano that was once a fixture in the WKMH studios. Robin’s WKMH vibe was showcased in the second of the Cruisin LP series, featuring WKMH and the year 1956.

“I always joked that we were number 11 in a 10 station market,” Robin said. “I told him, ‘Pat, I don’t much like the music or the format, but we have to become a top-40 station. It’s the future.’ Not too long after that, he paid a consultant named Mike Joseph 50 grand to do precisely what I had suggested at that dinner.”

And Keener was born.

“Since I had been around so long, my audience had aged and it was natural to slot me into the 9 to Noon spot. That’s where the housewives were and most of them had grown up listening to me. It was amazing to watch Keener grow so quickly in popularity and to be one of the original Key Men of Music.”

“The secret was the mixture of the music and the power of the personalities of the announcers,” Robin recalls. “Each of us had a special relationship with our audience. That no longer exists today.”

It was a situation that continued until Patterson asked Robin to make the choice, between radio and television. The program was originally called “Teen Town”, morphing away from an interview and information format into a showcase for popular music that became “Swingin’ Time” across the Detroit River at Windsor’s CKLW. Robin was hosting “Swingin’ Time” five days a week, taping a Saturday night show on Fridays. “I told ‘Pat’ that it was an ideal way to cross promote Keener to a TV audience that was right in our sweet spot,” Robin remembers. “But Walter held firm and I opted for TV. There were some scary moments, because I had given my notice before the RKO people in New York had okayed the show. Only a few days before my time was up at Keener I got the call to meet management at the London Chop House and learned that we had a deal.

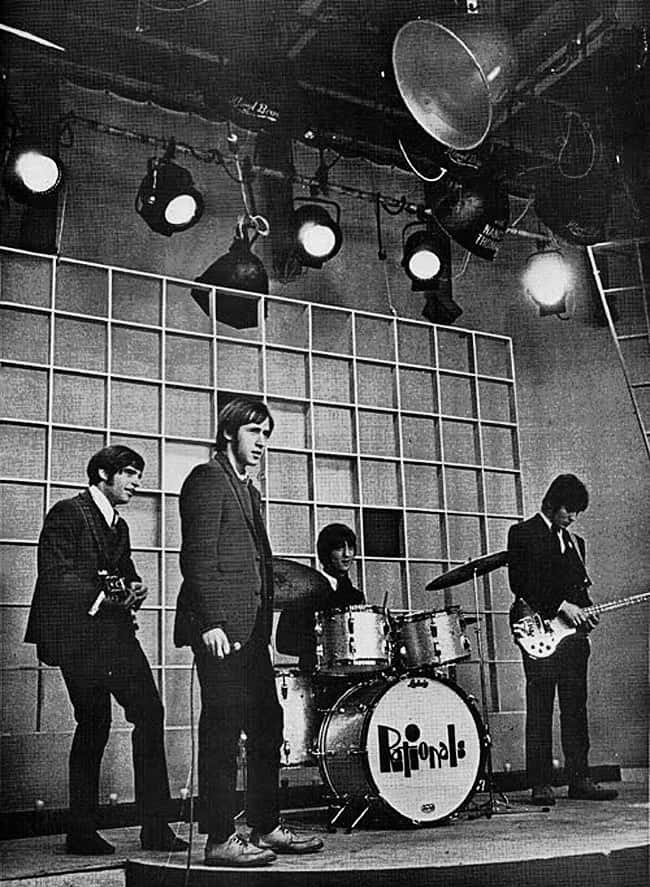

The “Swingin’ Time” brain trust included Art Cervi, another legendary name in Detroit media, who would become the person most Keenerfans remember as “Bozo, the World’s Most Famous Clown”. With Motown in the back yard and a large pool of Detroit musicians, “Swingin’ Time” ultimately attracted the attention of record companies, who supplied the biggest artists of the day and often watched the program to spot budding talent. “We had everyone from Bob Seger and the Rationals to Pat Boone and the Mothers of Invention,” Robin said.

One incident that he vividly remembers is Frank Zappa’s appearance on the program, where the iconoclastic performer unintentionally revealed a little too much of his physical attributes on live television. “The phones rang of the hook,” Robin said. “‘How could you allow something like that to go over the airwaves?’ was the common theme. It was proof that we had quite an audience.”

Robin continued with “Swingin’ Time” through the late 1960s before turning to direct marketing and ultimately to television production. Along the way, he tried his hand at managing the Detroit garage band “Sunday Funnies”, and struck up a lifelong friendship with “The Rationals” lead singer Scott Morgan. After relocating his production company to California, Robin became pioneer in the infomercial space, helping to generate over $40 million dollars in sales for a pain reliever called “Blue Stuff”. “For a time they were selling a million dollars worth of product a week,” Robin said. “Then the FTC started to question some of the claims they were making and the house of cards fell apart.”

Some of the stars Robin worked with during this time included Ernest Borgnine and Tipi Hedren. “Total professionals and wonderful people,” Robin remembers.

After a heart attack and surgery to implant two stents into his chest, Robin decided to close his company and move to Texas to be near his two daughters. As his generation began to pass on, friends pressed Robin to write his autobiography, a project that nears completion as this is being written. “If I had known in advance that it would have been this much work, I might not have done it,” he joked.

For those of us who grew up with him in Detroit, it’s will be an eagerly awaited trip down memory lane.