By the time we heard of Ozzy Osbourne’s passing at seventy-six, it felt less like the end of a life than the closing of a parable we’d been reading out loud for decades, unsure whether it was tragedy, farce, or miracle. His death on July 22nd was met with the kind of double take that only Ozzy could provoke: not he’s gone, but he wasn’t already? For most of his public existence, Osbourne seemed to teeter in a permanent twilight between collapse and comeback, a man whose biography was written in tabloid headlines and guitar feedback. That he lived as long as he did felt less like good fortune than a cosmic clerical error.

Osbourne’s improbable journey began in the soot-colored cradle of Aston, a working-class district in postwar Birmingham where the air smelled of iron and prospects were measured in shifts. From this gray terrain, he and his bandmates, Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler, and Bill Ward, conjured a sound that mirrored the environment: Black Sabbath’s music was loud, lumbering, and claustrophobically heavy. It wasn’t just rock; it was doom with a backbeat. Where the Beatles (Ozzy cheered Paul McCartney as an influence) had sung of submarines and revolutions, Osbourne intoned about war, madness, and Lucifer himself. If the hippies promised transcendence, Sabbath warned of what lay beneath the acid dream once it curdled.

Ozzy’s voice, piercing, nasal, untrained, unforgettable, became a clarion for the disenchanted. When WKNR-FM listeners discovered, Black Sabbath, it wasn’t the prettiest sound in rock, but it might have been one of the most honest. Ozzy’s vocals didn’t soar so much as haunt, like something channeled rather than sung. It was the voice of someone who’d seen too much and somehow lived to talk about it, though barely.

Offstage, Osbourne was often a contradiction wrapped in chaos. He could be feral, ridiculous, sometimes terrifying, and yet curiously innocent. Stories of his debauchery read like apocrypha, snorting ants, decapitating bats, urinating on the Alamo, yet the man himself rarely seemed malevolent. Instead, he often resembled a child who’d wandered into a horror movie and decided to stay. The world called him the Prince of Darkness, but anyone paying attention could see the fragility under the theatrics. He wasn’t the devil; he was the boy in his thrall.

The solo years, improbably, gave us the most refined version of the Ozzy myth. Teaming with guitarist Randy Rhoads, whose virtuosity elevated Osbourne’s raw power, he released Blizzard of Ozz and Diary of a Madman, records that not only cemented his legacy but also redefined what metal could be: grand, melodic, even beautiful in its brutality. These were not the desperate gasps of a fired frontman but the confident roars of an artist in full voice.

Then came the turn no one saw coming. In 2002, MTV’s The Osbournes reframed the singer’s life as sitcom. Here was Ozzy, not summoning Satan but mumbling through domesticity, mystified by technology and ankle-deep in dog waste. If Sabbath was an exorcism of industrial despair, The Osbournes was a meditation on entropy, what happens when the monster grows up and settles into a gated community. It was either the death of mystery or its next incarnation.

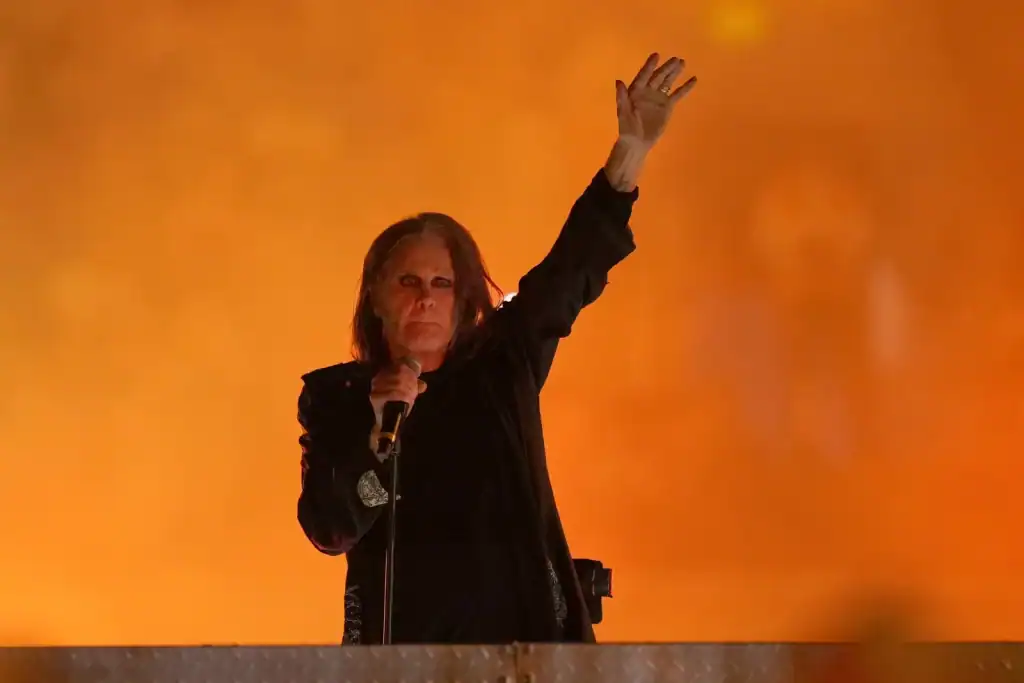

In his later years, Osbourne’s body betrayed him. A near-fatal ATV crash in 2003, followed by a Parkinson’s diagnosis and multiple surgeries, turned the once-indestructible rocker into a cautionary tale about gravity. And yet, he persisted. He kept showing up, on red carpets, in recording studios, occasionally on stage. Even when his spine seemed to fold under the weight of decades, he refused to bow. His final performance, a July 5th reunion with the original Black Sabbath in Birmingham, was a gesture of defiant symmetry: the beginning and the end, fused in one last ritual. He sang from a throne, regal and wrecked, a monarch of mayhem making peace with his kingdom.

Ozzy Osbourne’s legacy is inseparable from the contradictions he embodied. He was a carnival and a confessional, a terror and a teddy bear. He gave us music that made darkness a thing and showed us, through bumbling vulnerability, that monsters can be human, too. In the end, he didn’t just survive the wreckage of metal rock and roll, he became its patron saint, burned and bent but never buried.

His life was a noise, a spectacle, a sigh. And now, finally, a silence.