There was always a peculiar geometry to the music of Brian Wilson, a sense of vast, sun-bleached space being meticulously organized inside the four walls of a recording studio. To hear of his passing at eighty-two is to imagine the door to that studio finally closing, a quiet click after decades of miraculous, agonizing noise.

There was always a peculiar geometry to the music of Brian Wilson, a sense of vast, sun-bleached space being meticulously organized inside the four walls of a recording studio. To hear of his passing at eighty-two is to imagine the door to that studio finally closing, a quiet click after decades of miraculous, agonizing noise.

The news itself felt like one of his compositions: arriving with a surface simplicity that belied a profound, underlying ache. The architect of the California myth, the man who gave the American summer its official soundtrack, has fallen silent. But the structures he built—those towering cathedrals of harmony—remain, shimmering and permanent on the horizon of our memory.

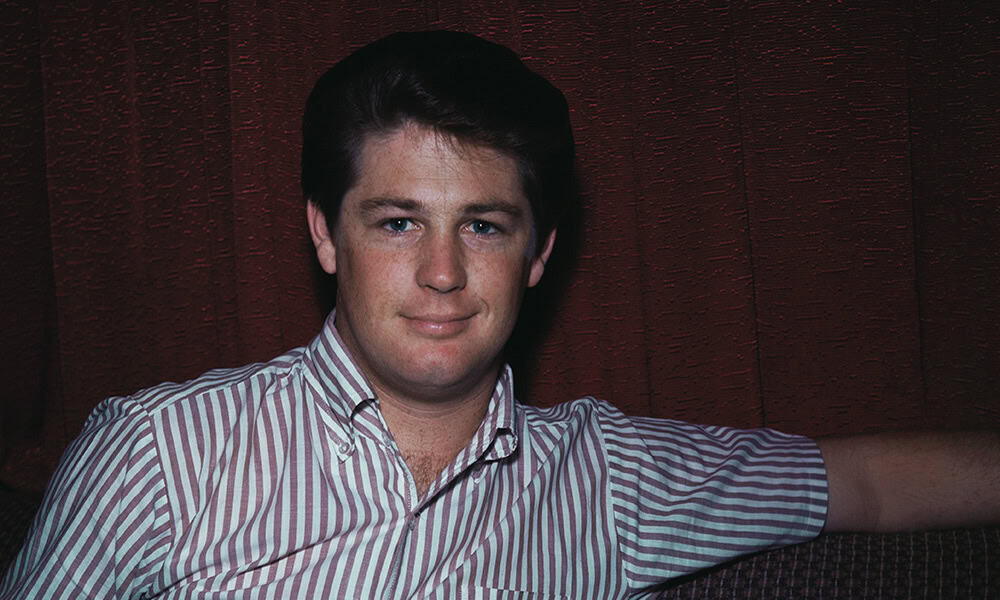

He was, from the start, a paradox: the homesick traveler in the land of fun. The early Beach Boys hits were brilliant feats of cultural cartography, mapping a nation’s idyllic fantasy of itself with two-minute bursts of genius. “I Get Around,” “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” “Fun, Fun, Fun”— a few of the 21 Beach Boy tunes which charted on Keener were not mere songs but destinations, delivered with a falsetto so pure it felt like an aspiration. Yet the cartographer himself was an indoor kid, a troubled soul with a damaged ear who found the crashing surf less inspiring than the intricate harmonies of the Four Freshmen. He was building a paradise he felt unfit to inhabit, and the tension between the joyful product and the anxious creator was the engine of his art.

That tension became the text with Pet Sounds. Spurred by the artistic leap of The Beatles’ Rubber Soul, Wilson turned his gaze inward, and the music followed. The album, released in 1966, was a pivot from declarative joy to interrogative vulnerability. He traded the certainties of the boardwalk for the deep ambiguities of the human heart. Using the session musicians of the Wrecking Crew as his orchestra, he composed with an alchemist’s touch, turning the base metals of pop into something golden, fragile, and deeply strange. On “God Only Knows,” he crafted what Paul McCartney would call the most perfect song ever written, a piece of music that holds a lover’s devotion and a spiritual seeker’s doubt in the same beautiful, trembling hand. He had created, as he famously said, “a teenage symphony to God,” and in its poignant silences, you could hear the sound of his own isolation.

If Pet Sounds was a prayer, Smile was a schism. The legendary unfinished album was an attempt to deconstruct pop music and reassemble it as a sprawling, kaleidoscopic vision of Americana. It was modular, mischievous, and so far ahead of its time that it broke time itself. The project’s collapse under the weight of its own ambition, coupled with Wilson’s deteriorating mental health and the incomprehension of his bandmates, is the central tragedy of his story. He flew too close to the sun, and for the next twenty years, he lived in the shadow of his own fall, a recluse haunted by the very music that was supposed to set him free.

The long wilderness that followed was a grim chapter, marked by stories of debilitating illness, immense weight gain, and the exploitative control of his therapist, Eugene Landy. Wilson became a byword for genius undone, a cautionary tale whispered in recording studios and rock-and-roll biographies. But what was mistaken for an ending was merely a protracted intermission. The slow, heroic climb back into the light, facilitated by the love and fierce protection of his wife, Melinda Ledbetter, is the testament to his life’s true meaning: survival.

His return to the stage was a thing of quiet bravery. He would sit at his piano, a fragile, almost translucent figure, surrounded by a band of brilliant young musicians who helped him carry the weight of his own creations. And then, in 2004, came the miracle. He revisited, reconstructed, and finally released Smile. It was more than a record; it was an act of reconciliation with his own ghost. To see him perform it was to witness a man turning his greatest trauma into a shared, cathartic triumph. The symphony was complete.

The tributes from his peers—McCartney, Elton John, Springsteen, Questlove—all circle the same essential truth: Brian Wilson was a harmonic pioneer who wrote the feelings that others could only grope for. He composed joy from a place of profound pain, built monuments to togetherness out of his own solitude. He was the lonely boy in the room who invited the whole world in to listen. Now that he is gone, we are left with that invitation, still echoing. He has left the studio, but the sound—his sound, that impossible blend of sunshine and sorrow—plays on, a chord that resolves into eternity.