When Beatlemania exploded on Keener, it wasn’t just a cultural phenomenon, it was a marketing war. On one side of the Atlantic stood EMI’s Parlophone label, helmed by producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick, who shaped the Beatles’ artistic journey with a balance of studio innovation and British sensibility. On the other, Capitol Records, EMI’s American subsidiary, played the hits game with a nose for profit. The result? Two Beatles discographies: one curated by the band and their producer, the other chopped, shuffled, and rebranded for U.S. ears.

When Beatlemania exploded on Keener, it wasn’t just a cultural phenomenon, it was a marketing war. On one side of the Atlantic stood EMI’s Parlophone label, helmed by producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick, who shaped the Beatles’ artistic journey with a balance of studio innovation and British sensibility. On the other, Capitol Records, EMI’s American subsidiary, played the hits game with a nose for profit. The result? Two Beatles discographies: one curated by the band and their producer, the other chopped, shuffled, and rebranded for U.S. ears.

And those differences? They tell a deeper story about the transatlantic tug-of-war between artistry and commerce.

The Frankenstein Approach

Let’s start with the obvious: The American Beatles albums we bought at Grinnell’s and Korvette’s before Sgt. Pepper were often completely different creatures than their British counterparts. Where EMI would release a 14-track LP with no singles (standard UK practice), Capitol leaned hard into the American formula—12 tracks per album, hit singles front and center. To fill out the release schedule and maximize profits, Capitol took liberties: cutting songs, remixing, and even adding artificial reverb to suit what they believed the American market wanted.

Take Rubber Soul. In the UK, it was a tight, folk-tinged turning point for the band—an introspective set of songs that began their transition from pop stars to studio auteurs. Capitol, sensing a Dylan-sized wave cresting in America, leaned into that vibe. They dropped four songs, added two from the earlier Help! sessions (including the acoustic “I’ve Just Seen a Face” as the opener), and created what many American fans believed was the definitive version. We perceived folk-rock magic—but it wasn’t what the Beatles intended.

Singles and Sacrifices

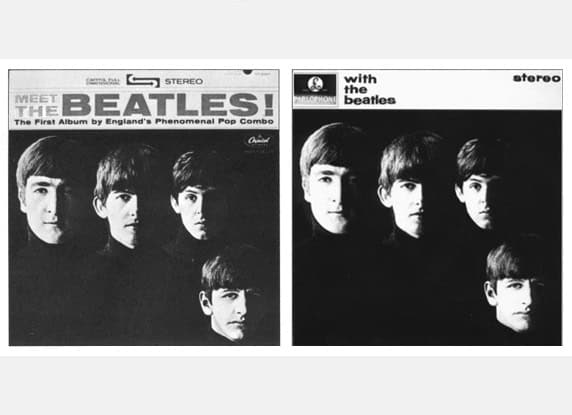

EMI’s policy kept singles off albums. “She Loves You,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” “Paperback Writer,” massive hits in Britain, weren’t on the UK LPs. In contrast, Capitol stuffed its albums with them. The label understood that U.S. teens bought albums for the hits. So singles and B-sides that were meant to stand alone in the UK were folded into LPs like Meet the Beatles! and Yesterday and Today.

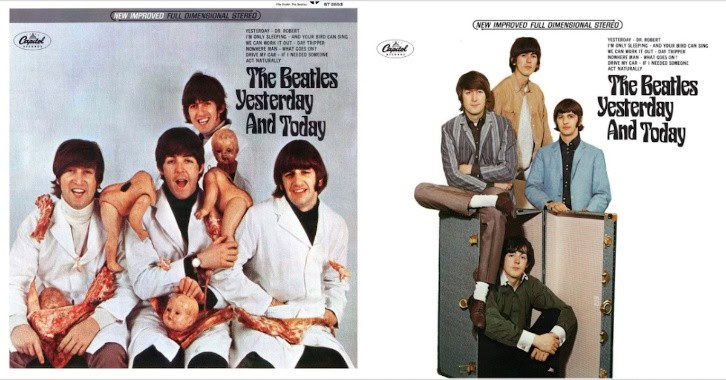

Capitol’s 1966 Yesterday and Today is perhaps the most infamous example—not just for its Frankensteinian track list (pulling from Help!, Rubber Soul, and Revolver), but for the notorious “butcher cover,” where the Fab Four posed with raw meat and dismembered dolls in protest of Capitol’s album-mangling.

The Beatles original cover sparked outrage and was quickly recalled by Capitol Records. It was replaced with a more conventional photo of the band posing around a steamer trunk, but not before a few thousand of the original “butcher covers” made it into circulation. Today, those rare copies are prized collector’s items and a lasting symbol of the Beatles’ growing defiance against industry control.

The band hated the Capitol system. “We put a lot of work into the sequencing,” John Lennon later said. “We didn’t like what Capitol was doing.” To the Beatles, these American releases were bastardizations.

Stereo Shenanigans

Then there’s the sound itself. Capitol engineer Dave Dexter Jr., who initially rejected the Beatles before relenting, had a fetish for echo chambers and reverb. His early Beatles LPs were soaked in reverb to mimic the lush sound of American rock ’n’ roll records. Songs like “I Feel Fine” and “She’s a Woman” were drenched in echo, giving them an unnatural sound the band approved.

Worse, Capitol often created “duophonic” or “fake stereo” versions by splitting mono tracks into separate channels and adding delay or EQ, sonic patchwork that makes audiophiles shudder today. The same was true for another Capitol client, The Beach Boys. It wasn’t until much later that we heard fuller stereo Beach Boy mixes on the ubiquitous CD box sets.

Two Narratives, One Legacy

So what’s the verdict? Were Capitol’s versions an act of vandalism, or savvy marketing that helped launch Beatlemania stateside?

The truth, like a Lennon-McCartney lyric, is more complicated. Capitol’s meddling arguably diluted the Beatles’ artistic intent, yet those American LPs, Meet the Beatles!, The Beatles’ Second Album, Something New, shaped how Keener kids experienced the Beatles: not as the polished auteurs of Abbey Road, but as a wild, energetic rock ’n’ roll band kicking down the doors of the Ed Sullivan Theater.

By 1967, the Beatles wrested back control. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was released the same in both countries, track-for-track, cover-for-cover. Capitol fell in line. The studio era had arrived, and there was no room left for remixing the message.

Final Cut

Today, the British discography is considered canon. When the Beatles’ catalog was remastered for CD and streaming, it was the EMI versions that got the royal treatment. But those Capitol albums, quirky, manipulated, rebellious, are a part of Beatles history too, and were released as single CDs during the emergence of that newer media. They are reminders that even the biggest band in the world had to fight for their vision.