To hear a Lou Christie song on Keener for the first time was to experience something more than sound—a kind of pop exclamation mark hurled through a world of four-part harmonies and teenage platitudes. In a musical landscape dominated by the earnest chin-stroking of folk singers and the tight, syncopated machinery of Detroit’s Motown, Christie’s voice arrived like a lightning strike, cutting clean through the Keener airwaves. It was a helium-soaked, heaven-scraping falsetto that didn’t so much sing as spiral—vertiginous, improbable, and entirely unafraid of absurdity. It sounded less like a young man’s croon than the internal monologue of adolescence itself: dramatic, operatic, always on the verge of a glorious crack-up.

To hear a Lou Christie song on Keener for the first time was to experience something more than sound—a kind of pop exclamation mark hurled through a world of four-part harmonies and teenage platitudes. In a musical landscape dominated by the earnest chin-stroking of folk singers and the tight, syncopated machinery of Detroit’s Motown, Christie’s voice arrived like a lightning strike, cutting clean through the Keener airwaves. It was a helium-soaked, heaven-scraping falsetto that didn’t so much sing as spiral—vertiginous, improbable, and entirely unafraid of absurdity. It sounded less like a young man’s croon than the internal monologue of adolescence itself: dramatic, operatic, always on the verge of a glorious crack-up.

The Choirboy from Glenwillard

That voice belonged to Lugee Alfredo Giovanni Sacco, a choirboy from Glenwillard, a small Pennsylvania town better known for steel mills and freight yards than musical theater. But Lugee, reborn as Lou Christie, had ambitions loftier than the top 40—ambitions rooted not in rock ’n’ roll rebellion but in something closer to Italian opera. While his contemporaries drew their swagger from Elvis, Christie studied vocal technique with a near-religious discipline. His songs, and his entire career, reflected this tension between teen idol and torch singer, between street-corner doo-wop and La Scala.

His songwriting partner, Twyla Herbert, was as unlikely as his voice. A classically trained pianist and self-described mystic nearly thirty years his senior, Herbert was part eccentric aunt, part spiritual conductor. From her Pennsylvania living room—cluttered with sheet music and astrological charts—the pair composed miniature melodramas in the guise of pop records. Their first hit, “The Gypsy Cried,” recorded on a shoestring budget in 1962, was a ghostly wail masquerading as a teen lament. It was followed by “Two Faces Have I,” a song whose harmonies trembled with inner conflict, its falsetto hovering just above despair.

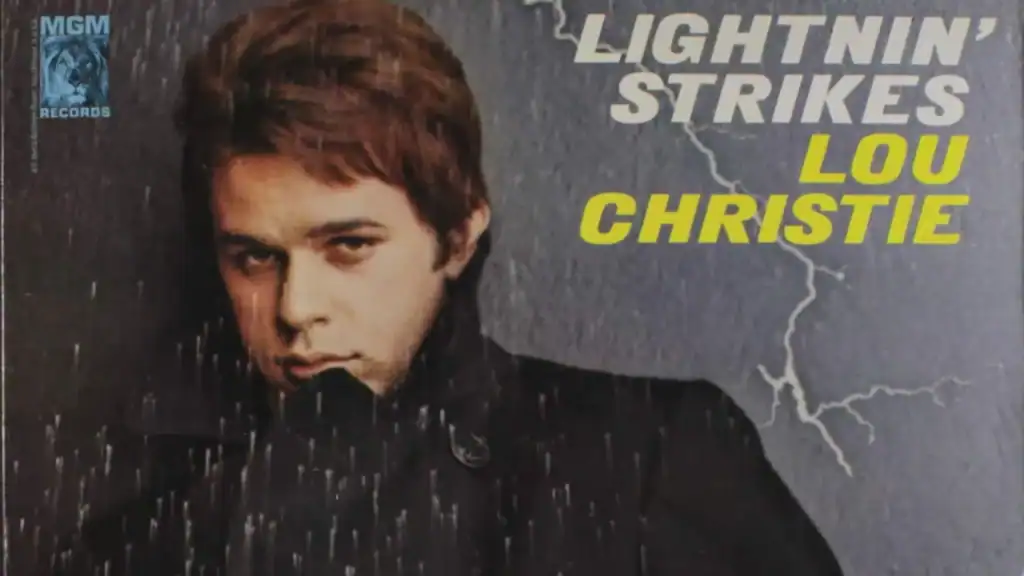

Catching Lightning in a Bottle

But it was in 1966, with “Lightnin’ Strikes,” (Keener Hit #1 – 12/29/1965) that Christie achieved pop divinity. The record opens with a confident, near-spoken verse—a swaggering prelude to the emotional cataclysm ahead. Then, with a thunderclap of drums, his voice detonates. It climbs and climbs, launching itself into the upper atmosphere like a bottle rocket with a broken parachute. “When I see lips beggin’ to be kissed…”—the line doesn’t resolve so much as combust. That the song reached Number One on the Billboard Hot 100 is less surprising than the fact that anything so weird, so breathless and bombastic, ever got recorded at all.

He followed that blast of adolescent id with “Rhapsody in the Rain,” (Keener Hit #25 – 4/13/1966) a backseat confession so steamy that some radio stations across the country pulled it from rotation. “We were makin’ out in the rain,” he moaned, as pianos mimicked windshield wipers and thunder growled in the background. In an era still straining toward sexual euphemism, Christie’s record was so explicit in tone and atmosphere that it felt less like a song than an overheard memory.

Christie’s trajectory was rarely smooth. After a brief early chart run, his career was interrupted by a two-year stint in the Army, often a kiss of death for a pop star. But he returned stronger, stranger, and somehow more himself, reflected in “I’m Gonna Make You Mine” Keener Hit #11 – 8/14/1969. He was never an industry puppet. He wrote his own material, crafted his own sound. He was one of the first of pop’s true singer-songwriters, though this fact is often lost beneath the glitter of his falsetto.

Famous Friends and Enduring Appeal

His influence endured in unexpected corners. In the early seventies, Christie spent time recording in London, where a young session pianist named Reginald Dwight, soon to be Elton John, played on his tracks. John Lennon praised his artistry. Decades later, Madonna, in the liner notes to The Immaculate Collection, offered a surprising thank-you to Lou Christie. He was, quietly, a musician’s musician.

He may have drifted from the charts but he never fully left the stage. The oldies circuit embraced him, and his voice, even into his seventies, retained its daring elasticity. In his final years, he lived in New York City’s Hell’s Kitchen, a genial elder statesman of a pop world he had once electrified. He remained a presence; stylish, wry, in love with the city and the music that had given him everything.

When Lou Christie died this morning at the age of eighty-two, we lost not only a survivor of the Keener era but one of our most idiosyncratic visionaries. He was that rarest of pop artists: a genuine auteur disguised as a chart act. He brought theater to the transistor radio. He made drama out of desire.

And in those three minutes of vinyl, those operatic crescendos of heartbreak, lust, and longing, he gave voice to the magnificent, mortifying excesses of youth.

He was Lugee Sacco, the choirboy who dared to fly close to the AM Radio sun. For the Keener generation, he will always be remembered as Lou Christie, and for that brief, perfect moment when the sky was his.