The events that come to define us are rarely the result of careful planning. They are often the unexpected dividends of serendipity. For Bob Green, the path to the Detroit broadcasting began not in a radio control room, but in the frustrating confines of Antoinette Hondelink’s high-school math class. Robert Greenstone possessed an architect’s eye for structure and a desire to wrestle glass, steel, and stone into a symphonic whole.

But geometry proved to be the barrier between Bob and the world of Frank Lloyd Wright. Stymied by cosines and vectors, he found his fascination drifting toward the ether, specifically, technology that could translate the human voice into iron particles arranged neatly along the Mylar of a neighbor’s Webcor tape recorder.

It was a serendipitous deflection. In the mid-nineteen-fifties, Bob found himself at Bard College, a liberal-arts institution perched on the Hudson River. He answered a bulletin board summons to join the campus radio station, WXBC.

He had barely secured the position when the dormitory housing the studio burned to the ground. By the time the facilities were reconstructed, the staff of twenty-two enthusiasts had dwindled to a quartet, leaving Bob effectively in charge of a home-brew operation that would unwittingly serve as the blueprint for a career.

“When we finally rebuilt, we had a ten-watt transmitter that was supposed to send the signal to the dormitories.” Impatient for the official hook-up, Bob, a ham radio enthusiast, strung a wire across the athletic fields. He connected it to the transmitter and fired up a tape of his show. He then drove his 1951 Ford twenty miles down Route 9 to Kingston, New York, just to hear his own voice crackling over 630 AM.

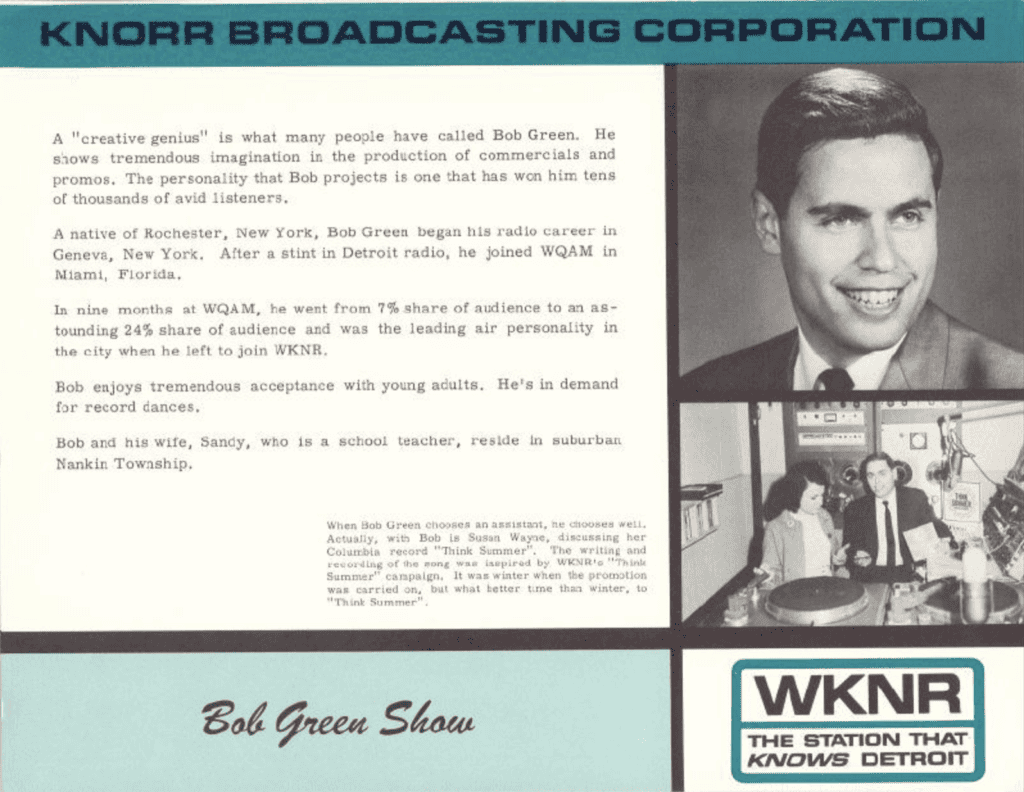

Bob’s apprenticeship was served in the chaotic trenches of upstate New York radio. At WSAY in Rochester and WGVA in Geneva, he emulated the polished baritones he heard on Boston’s WBZ.

But the siren song of Detroit was already whispering. Attracted by a tape of jingles using the call letters WKMH, Bob set his sights on the Motor City. The station, however, was not yet ready for the revolution. Bob, ever in search of the best, took a detour to Miami. WQAM was a Storz station, as in Todd Storz, one of the inventors of the Top 40 format.

If upstate New York was the wilderness, Miami was a white-hot finishing school. WQAM possessed a legendary, reverb-laced, compressed sound that would come to define the rock radio of the sixties. Many familiar Keener names, Jerry Goodwin, Ted Clark and “Rock Robins,” who would become Scott Regen were sharpening their skills in the sunshine.

It could also be a trial by fire. During his first on-air shift, a typical South Florida thunderstorm caused a power flicker that sent the station’s wall of automated tape machines into rewind mode, live on the air. Unable to play music, Bob opened the phone lines, turning a technical disaster into an impromptu talk segment until an engineer could coax the complex collection of technology back to life. It was a lesson in adaptability that would become a key ingredient of his future success.

When WKMH finally decided to embrace the rock-and-roll zeitgeist, Bob headed back to the Motor City. The station was rebranded WKNR, or “Keener 13,” a moniker that stuck with the tenacity of a Brill Building hook. While Detroit’s competing radio properties were still collections of individual personalities, Keener over came a weak signal and complex antenna array that made the station inaudible in many corners of Detroit after dark, to offer a unified brand, a consistent sound that listeners locked onto despite it’s limited technical faculties.

The secret was a philosophy Bob termed “Intelligent Flexibility.” In an industry increasingly dominated by rigid formatting, he and program director Frank Maruca encouraged their “Keymen” to take risks.

“The format was there to serve us,” he told me. “We weren’t there to serve the format.”

This allowed for moments of spontaneous brilliance, such as Scott Regen’s “Groove Yard,” and The Burger Club, Gary Stevens’ “Wollyburger,” J. Michael Wilson’s “Rodney the Rodent,” and Dick Purtan’s ad-libbed comedy. Each forged a connection with listeners that transcended the music itself.

By the late sixties, the landscape was shifting. The rise of FM and the arrival of the sleek, “Drake” format with CKLW’s 50,000 watts behind it, began to erode Keener’s dominance.

“I had just built a house,” Bob remembered, wryly noting the industry superstition that such an act is the “kiss of death.” Consultants returned to 15001 Michigan Avenue, the marquee talent was fired to bring equilibrium to the balance sheet, and the unique, chaotic magic of Keener was slowly streamlined into oblivion.

Bob moved to Houston, ultimately establishing a successful production house, But the ghost of Keener 13 persisted. At a reunion in 1988, he was swarmed by fans, a testament to the station’s enduring grip on the local psyche. In a post-9/11 world, Bob sensed this nostalgia was a desire to hold onto a time when the voice on the radio felt less like a distant announcer and more like a friend in the passenger seat.

You could hear it’s cadence in the plethora of commercials Bob Green Productions created for clients across the country.

We who in turn emulated Bob’s high-energy-smooth style found a kind and generous mentor who could give you sometimes tough developmental feedback in a way that inspired you to raise the bar.

“How would Keener do it?” became a universal question, even as Steve and I took detours from broadcasting into other corners of the corporate world.

Bob was an attentive friend who called with regularity, “Just to see how you’re doing,” and who would stop by our house when he and his wife, Sandi, were within hailing distance.

For two years, the stewards of the 1310 AM frequency gave us permission to bring Keener back to life for the annual Woodward Dream Cruise Weekend. Bob generously contributed a custom hour to the proceedings. I replay those recordings on Keener13.com every August. Bob sounds just as fresh, decades later.

When we came up with the idea of a tribute website, Bob was the first to share his treasure trove of material. When he downsized his studios, Bob gave us hundreds of original tapes from his collection. He helped me tweak the modern-day version of Keener 13 which Steve and I kept under the radar until we were satisfied it was ready for prime time.

Another dimension of Bob’s wisdom: Never let the allure of stardom diminish important relationships. In a world where marriages struggle to compete with fandom, Bob was a true family man. Sandi’s passing left an emptiness I could hear whenever we talked.

Yet Bob continued make the trip from Texas to every Detroit radio reunion. The surviving talent and we awe struck fans surrounded him to feel the humility and personal attention that always radiated from his being.

Keener’s blend of high energy and human connection seems almost anachronistic in an age of algorithmic playlists. But for a few golden years in Detroit, Bob Green and his cohorts built something that stood as tall and imposing as any skyscraper: An auditory experience that was truly the heartbeat of a city. Six decades after Keener’s Halloween Night birthday, the brand remains central to the soundtrack of a generation.

Bob’s passing, after a long life well lived, is still a gut punch. The loss of a patriarch. A role model we continue to emulate. In the outposts where radio is still an art form, Bob Green’s influence is still felt. Listeners are still magnetically drawn toward the humanity beyond the music.

Our world is still Keener. And the architect lives on.