Mark Volman (1947–2025): A Requiem in Technicolor

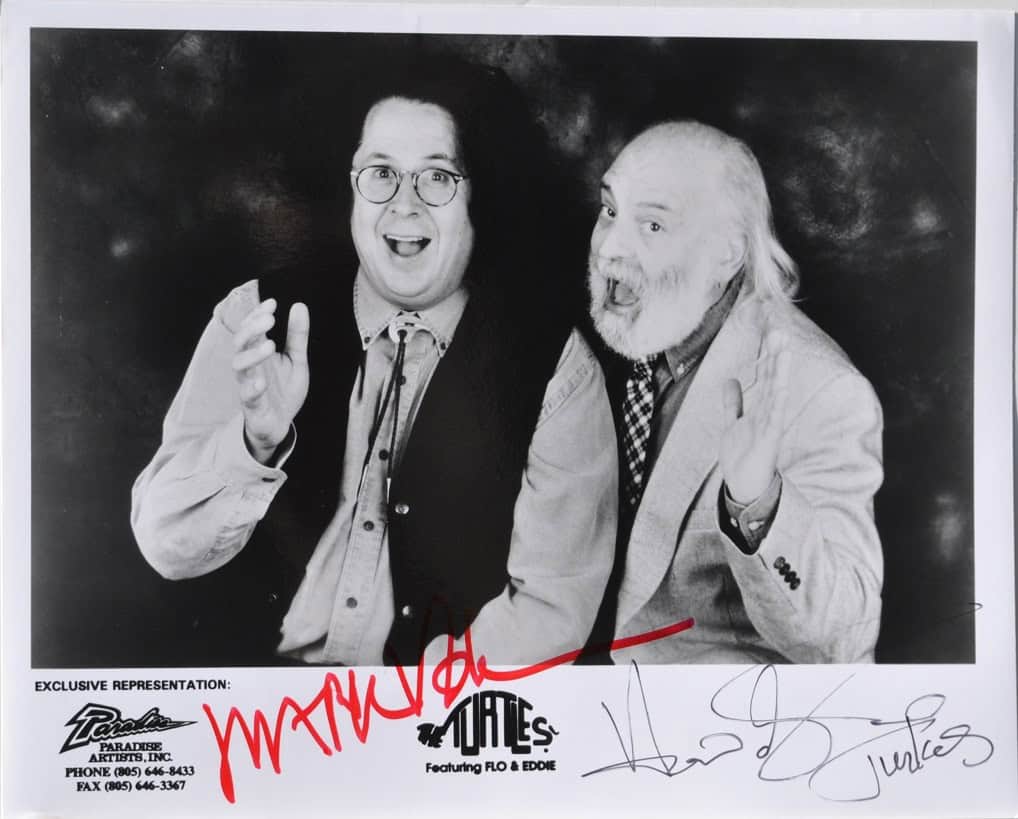

Mark Volman, the curly-haired frontman of The Turtles, breathed his last in Nashville after a brief, unexpected illness. He was 78 years old.

Volman was born on April 19, 1947, in Los Angeles, where the Pacific sun and boisterous city life infused him with a lively spirit. It never abated. As he recalled, he met his lifelong partner in harmony, Howard Kaylan, in Westchester High’s choir; together, they graduated in 1965 and swiftly formed a band that would become The Turtles.

They were not just another sixties band. They were masters of melodic alchemy, taking folk, surf, and psychedelia, and mixing them into radio-ready delights: “It Ain’t Me Babe,” “Elenore” and, of course, the immortal Happy Together, a song whose grace belied the complex chords beneath. The tune became the summer anthem on Keener in 1967 that still populates air-checks today.

When The Turtles disbanded at the dawn of the seventies, Volman and Kaylan metamorphosed into Flo & Eddie, joining Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention and spreading their irreverent vocal alchemy across albums by T. Rex and Bruce Springsteen and on children’s television. Do yourself a favor and listen to the re-imagination of “Eleanore” on the Flo & Eddie “Moving Targets” LP. It’s a hot-rockin, danceable rendition that summarizes the irreverent party vibe we’ll always associate with their attitude.

If there was one word that captured Volman’s presence on stage, on record, in classrooms, in his memoir It was joy. Search YouTube for the Turtles’ playful performance on th Mike Douglas show. Mark was clearly there for the fun of it, playing or faking whatever instrument was thrust into his hands.

Even after his diagnosis with Lewy body dementia in 2020, a progressive illness that he publicly shared in 2023, his spirit remained irrepressible. He continued to tour under the “Happy Together” banner, leading revues of nostalgia and exuberance, refusing to let his voice fade. “Okay, whatever’s going to happen will happen, but I’ll go as far as I can,” he told People magazine with quiet determination.

Beyond his musical life, Volman embraced the academic rigor of storytelling. In his mid-forties, he returned to school, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in screenwriting from Loyola Marymount University. His commencement valedictory, delivered to the melody of Happy Together, earned him a moment on CBS Evening News. Eventually, he taught music business and entertainment industry courses at Belmont University in Nashville, where students affectionately called him “Professor Flo.”

His memoir, Happy Forever: My Musical Adventures With The Turtles, Frank Zappa, T. Rex, Flo & Eddie, and More, published in 2023, reads like a love letter to the counterculture, the road, and the absurd joys of backstage moments. There, he revisited tales of wild nights with Jimi Hendrix and John Lennon, the quirky battles over band names that morph into identity, and the halting triumph of reclaiming The Turtles name itself.

At the end, Volman’s final days were threaded with tenderness. Emily Volman, his partner, spoke of his “big old smile even at the end,” and how despite fatigue and hospital visits, he remained playful, humorous, and serenely optimistic. He died, as he lived, with artistry, warmth, and a smile.

He is survived by Emily; his former wife Pat Volman; daughters Hallie and Sarina; and his brother Phil.

We’re seeing the inevitable passing of the voices who intoned the soundtrack of our lives. Volman’s marks the closing of a chapter in American music that wrote itself in smile-lines, tambourine swirls, and harmonies that echo in sleep-filled minds. He was, in every sense, a joyful force. A bearer of buoyancy in an often-bleak world.

He would want us to imagine him onstage once more: Technicolor shirt, curls bouncing, singing, lighting a thousand faces with anticipation. That memory, bright and crackling, may be gone from the physical stage, but the resonance as he’d say… that stays.

The Classic

Fred Jacobs announced he has Parkinson’s in the same way he’s announced everything of consequence across a long, inventive career: plainly, without preamble, no tease for a later reveal after five minutes of spots for sports betting apps or cryptocurrency. It was Fred at his best, direct, unvarnished, and unwilling to pretend that candor requires theatrics. The news landed with the familiarity of a mentor once again pointing to the heart of the matter: here’s what you need to know, here’s what I’m doing about it.

Fred Jacobs announced he has Parkinson’s in the same way he’s announced everything of consequence across a long, inventive career: plainly, without preamble, no tease for a later reveal after five minutes of spots for sports betting apps or cryptocurrency. It was Fred at his best, direct, unvarnished, and unwilling to pretend that candor requires theatrics. The news landed with the familiarity of a mentor once again pointing to the heart of the matter: here’s what you need to know, here’s what I’m doing about it.

It was the same pedagogy he once used to teach young broadcasters the intricacies of tape and turntables. Here’s a splicing block, a razor blade, and a Moody Blues track, see if you can make it better. A lesson in craft disguised as a challenge in curiosity. Fred, after all, has always been animated by the tension between data and instinct, by the question of how a well-placed song, a novel sequence of sounds, could hold a listener for just a little longer.

He came of age in Detroit at a moment when progressive radio was a messy, fertile experiment, a laboratory disguised as a marketplace. The city was large enough to matter, but still porous enough that a DJ with conviction could elevate a local B-side into national phenomenon. From this improvisational chaos Fred distilled order, birthing the Classic Rock format. Its endurance is proof of his insight: the Super Bowl commercial scored with Led Zeppelin riffs, the teenager who can recite Aerosmith lyrics decades after release, the playlists that still map our cultural memory.

And yet Fred has never succumbed to nostalgia. He understood earlier than most that formats calcify, that what is “unique” in one decade becomes the background noise of the next. His daily missives to the industry were reminders that the business was never about quarterly cash flow, but about human connection. The best jocks weren’t commodities; they were friends in the ether, their voices tying the day together as surely as the verses in any hit single. When consolidation stripped those voices in favor of balance sheets, Fred noted, gently but firmly, that something essential was being lost.

He adapted. He founded a consultancy with his brothers, brought his flock to CES to imagine the future, and made a practice of asking questions that nudged the industry past its blind spots. He was not content merely to observe; he wanted to see.

So, it is no surprise that his confrontation with Parkinson’s is framed not as tragedy, but as another invitation to engage. First, name the fear. Second, gather every shard of knowledge about it. Third, reinvent. Parkinson’s, in this light, is not an end to curiosity but a new context for it.

Fred has long argued that profit and ratings are effects, not causes. The cause is value, what can be created, added, shared today, and how it might expand tomorrow. That belief has been his quiet mantra, animating both the stations he shaped and the people he mentored. His disclosure, delivered with characteristic candor, is simply another iteration of that same philosophy: authenticity first, because that is where trust lives.

In this, Fred remains the quintessential broadcaster, not just a curator of music, but a model for how to live with honesty and imagination. Perhaps the most important lesson he teaches is not about splicing tape, not about audience research, not even about Classic Rock. It is this:

Confront change, with all its peril and possibility. Speaking it aloud, and then imagine what treasures can yet be created.

The Quiet Orbit of Loni Anderson

For those of us who grew up addicted to broadcast radio, with its open mics and closed-door politics, “WKRP in Cincinnati” offered both affection and satire. And in that sound booth of a sitcom, no one held the frequency quite like Loni Anderson, who left us this weekend at age 79. As Jennifer Marlowe, the station’s receptionist, gatekeeper, and quiet oracle, Loni brought an impeccable poise to the role, turning what might have been just another dumb blonde into a strategic triumph, a lesson in misdirection, elegance, and the sly power of feminine competence. Continue reading “The Quiet Orbit of Loni Anderson” →

For those of us who grew up addicted to broadcast radio, with its open mics and closed-door politics, “WKRP in Cincinnati” offered both affection and satire. And in that sound booth of a sitcom, no one held the frequency quite like Loni Anderson, who left us this weekend at age 79. As Jennifer Marlowe, the station’s receptionist, gatekeeper, and quiet oracle, Loni brought an impeccable poise to the role, turning what might have been just another dumb blonde into a strategic triumph, a lesson in misdirection, elegance, and the sly power of feminine competence. Continue reading “The Quiet Orbit of Loni Anderson” →

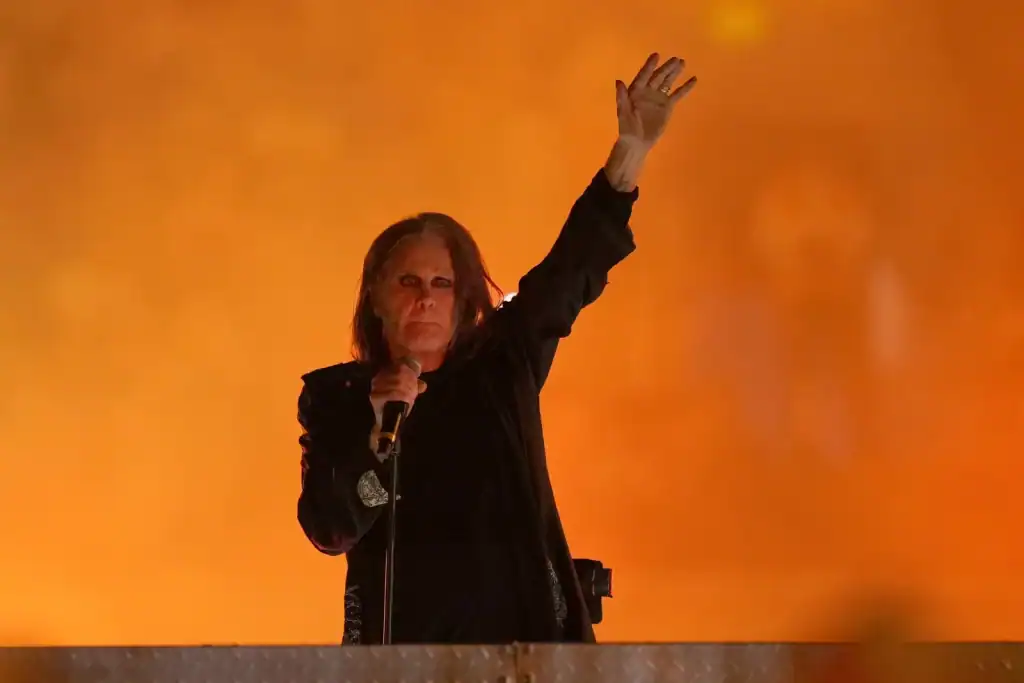

Ozzy Osbourne Courted Darkness and Outlived It

By the time we heard of Ozzy Osbourne’s passing at seventy-six, it felt less like the end of a life than the closing of a parable we’d been reading out loud for decades, unsure whether it was tragedy, farce, or miracle. His death on July 22nd was met with the kind of double take that only Ozzy could provoke: not he’s gone, but he wasn’t already? For most of his public existence, Osbourne seemed to teeter in a permanent twilight between collapse and comeback, a man whose biography was written in tabloid headlines and guitar feedback. That he lived as long as he did felt less like good fortune than a cosmic clerical error. Continue reading “Ozzy Osbourne Courted Darkness and Outlived It” →

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Ringo

On the seventh of July, a Monday, amidst the unassuming hum of a world carrying on, Richard Starkey, saw his eighty-fifth year. The name he would later adopt—Ringo Starr—needs, of course, no introduction, yet it is the given name that feels more appropriate for the quietude of the occasion. If the Beatles were a singular, four-headed marvel of the twentieth century, then Ringo was its circulatory system—unshowy, indispensable, and possessed of a swing that was as intuitive as a heartbeat. Continue reading “The Unbearable Lightness of Being Ringo” →

On the seventh of July, a Monday, amidst the unassuming hum of a world carrying on, Richard Starkey, saw his eighty-fifth year. The name he would later adopt—Ringo Starr—needs, of course, no introduction, yet it is the given name that feels more appropriate for the quietude of the occasion. If the Beatles were a singular, four-headed marvel of the twentieth century, then Ringo was its circulatory system—unshowy, indispensable, and possessed of a swing that was as intuitive as a heartbeat. Continue reading “The Unbearable Lightness of Being Ringo” →

AT 40 at 55

On the Fourth of July weekend in 1970, America was still catching its breath from the cultural detonation of the previous decade. A new program came to life on just seven radio stations. “Here we go with the Top 40 hits of the nation this week on American Top 40,” the voice intoned. “The best-selling and most-played songs from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from Canada to Mexico.” It didn’t sound like revolution. It sounded like reassurance. Continue reading “AT 40 at 55” →

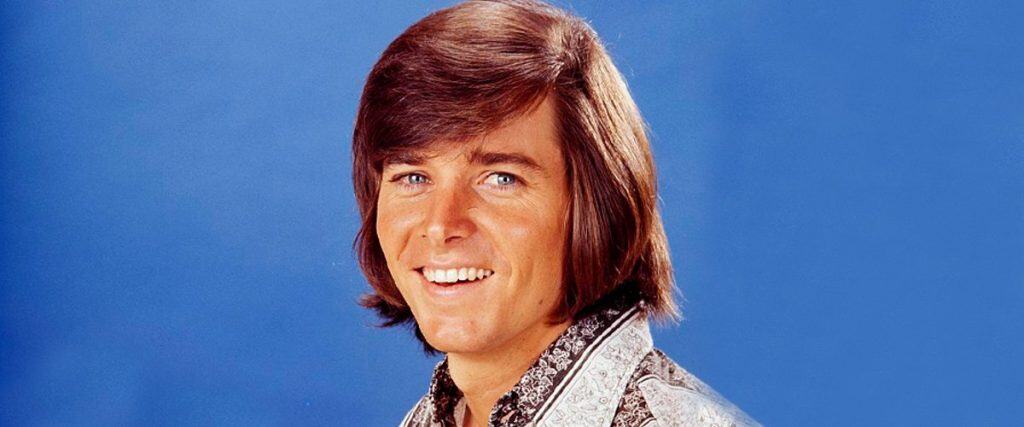

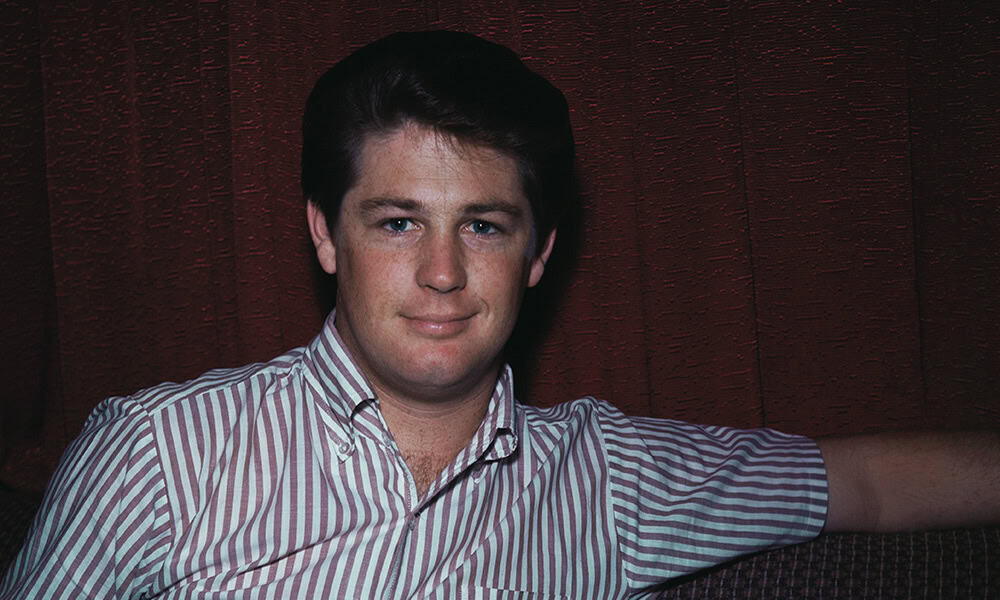

Bobby Sherman – A Quiet Finale

By June 24, 2025, the world had fallen silent—not with the frenzy that once trailed him, but with a gentle stillness. Bobby Sherman, the sweet-faced teen idol of the late 1960s, died at 81, his final days marked by the same modest grace that shaped his life. Continue reading “Bobby Sherman – A Quiet Finale” →

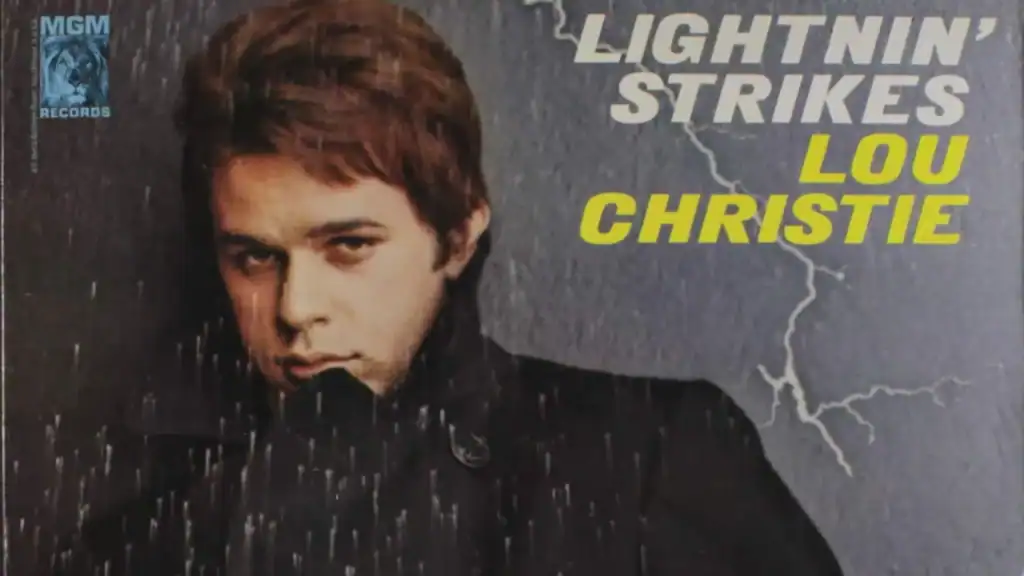

Lou Christie – The Voice That Pierced the Sky

To hear a Lou Christie song on Keener for the first time was to experience something more than sound—a kind of pop exclamation mark hurled through a world of four-part harmonies and teenage platitudes. In a musical landscape dominated by the earnest chin-stroking of folk singers and the tight, syncopated machinery of Detroit’s Motown, Christie’s voice arrived like a lightning strike, cutting clean through the Keener airwaves. It was a helium-soaked, heaven-scraping falsetto that didn’t so much sing as spiral—vertiginous, improbable, and entirely unafraid of absurdity. It sounded less like a young man’s croon than the internal monologue of adolescence itself: dramatic, operatic, always on the verge of a glorious crack-up. Continue reading “Lou Christie – The Voice That Pierced the Sky” →

To hear a Lou Christie song on Keener for the first time was to experience something more than sound—a kind of pop exclamation mark hurled through a world of four-part harmonies and teenage platitudes. In a musical landscape dominated by the earnest chin-stroking of folk singers and the tight, syncopated machinery of Detroit’s Motown, Christie’s voice arrived like a lightning strike, cutting clean through the Keener airwaves. It was a helium-soaked, heaven-scraping falsetto that didn’t so much sing as spiral—vertiginous, improbable, and entirely unafraid of absurdity. It sounded less like a young man’s croon than the internal monologue of adolescence itself: dramatic, operatic, always on the verge of a glorious crack-up. Continue reading “Lou Christie – The Voice That Pierced the Sky” →

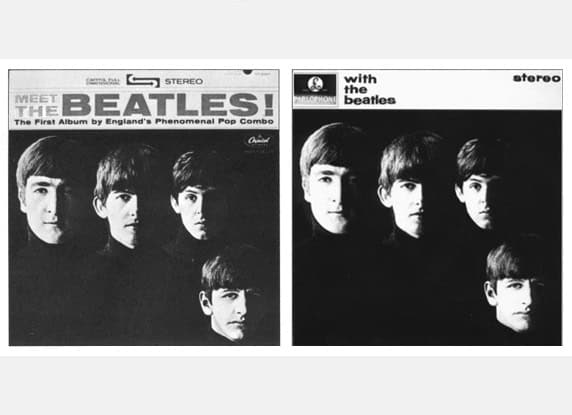

The Beatles’ EMI vs. Capitol Albums: How America Remixed the British Invasion

When Beatlemania exploded on Keener, it wasn’t just a cultural phenomenon, it was a marketing war. On one side of the Atlantic stood EMI’s Parlophone label, helmed by producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick, who shaped the Beatles’ artistic journey with a balance of studio innovation and British sensibility. On the other, Capitol Records, EMI’s American subsidiary, played the hits game with a nose for profit. The result? Two Beatles discographies: one curated by the band and their producer, the other chopped, shuffled, and rebranded for U.S. ears.

When Beatlemania exploded on Keener, it wasn’t just a cultural phenomenon, it was a marketing war. On one side of the Atlantic stood EMI’s Parlophone label, helmed by producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick, who shaped the Beatles’ artistic journey with a balance of studio innovation and British sensibility. On the other, Capitol Records, EMI’s American subsidiary, played the hits game with a nose for profit. The result? Two Beatles discographies: one curated by the band and their producer, the other chopped, shuffled, and rebranded for U.S. ears.

And those differences? They tell a deeper story about the transatlantic tug-of-war between artistry and commerce. Continue reading “The Beatles’ EMI vs. Capitol Albums: How America Remixed the British Invasion” →

Remembering Brian Wilson

There was always a peculiar geometry to the music of Brian Wilson, a sense of vast, sun-bleached space being meticulously organized inside the four walls of a recording studio. To hear of his passing at eighty-two is to imagine the door to that studio finally closing, a quiet click after decades of miraculous, agonizing noise. Continue reading “Remembering Brian Wilson” →

There was always a peculiar geometry to the music of Brian Wilson, a sense of vast, sun-bleached space being meticulously organized inside the four walls of a recording studio. To hear of his passing at eighty-two is to imagine the door to that studio finally closing, a quiet click after decades of miraculous, agonizing noise. Continue reading “Remembering Brian Wilson” →

Keener Today – June 3

It was a rare moment in time when Steve Schram and I were in the same place without anyone demanding our time. We were both independent agents with a lot more resume paragraphs ahead of us. As was our practice during the days when we roomed together in college, we were sifting through my collection of 45s and reel to reel tapes. Around 3am on June 3, 2002, I threaded the PAMS Clyde jingle demo into the machine and turned up the volume. Continue reading “Keener Today – June 3” →

Keener Today – May 24

Today in History:

- 1844 – Samuel F.B. Morse gave the first public demonstration of his telegraph by sending a message from the Supreme Court Chamber in the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. to the B&O Railroad “outer depot” (now the B&O Railroad Museum) in Baltimore. The famous message was, “What hath God wrought?” Continue reading “Keener Today – May 24” →